Forging the Path to the Carolina Thread Trail

Weaving philanthropy, leadership and collaboration for civic change

Bart Landess has noticed one key difference for the Carolina Thread Trail from when it was first proposed in the early 2000s and now.

“People said, ‘I don’t want a trail running through my property,’” recalled the CEO of the Catawba Lands Conservancy and Carolina Thread Trail. “Now they’re saying, ‘Can we please have a trail?’”

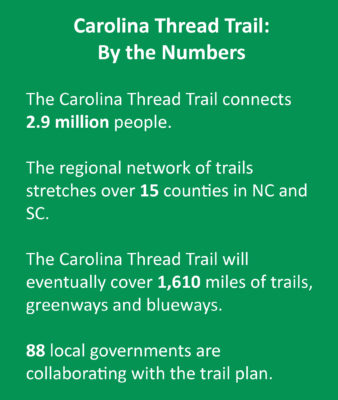

That’s because, with a footprint that now spans 15 counties – and a plan that will eventually spread it over 1,600 miles – the Carolina Thread Trail has quieted even the most vocal “not in my backyard” critics.

The Anne Springs Close Greenway is part of the Carolina Thread Trail.

The Carolina Thread Trail was also one of the first major civic initiatives undertaken by Foundation For The Carolinas. And the model used to create the trail – studying an issue, building early awareness and buy-in, fostering stakeholder engagement and partnerships, and securing funding to set a project up for long-term success – would be replicated time and again through FFTC’s Robinson Center for Civic Leadership.

The lessons learned through the Carolina Thread Trail would propel some of the community’s most impactful civic initiatives for years to come.

No clear path

The Foundation’s focus in its early years was primarily on one pillar: helping philanthropists manage their charitable dollars. But in 2004, FFTC’s governing board appointed a committee, chaired by philanthropist Sally Robinson and former Mayor Harvey Gantt, to explore the notion of adding a second pillar of focus in civic leadership.

“Civic leadership had long been a high-priority of Foundation For The Carolinas,” said Ruth Shaw, FFTC Governing Board chair, 2004-2005. “A study, led by our board, recognized that was an ongoing need, to have a sustainable approach to problem solving.”

“It became apparent these problems would not be totally solved by the public sector, and they wouldn’t be totally solved by the private sector,” said Gantt, FFTC Governing Board chair, 2005-2007. “What we needed was a neutral space where we could look for solutions.”

The goal through this second pillar – and the point of civic leadership – would be to position FFTC as a community consensus builder to address the region’s greatest challenges. Through pooling ideas, resources and talent, the Foundation’s civic leadership work could help the region capitalize on its most impactful opportunities.

“Civic engagement leads to civic leadership, if you take it and run with it,” said Michael Marsicano, FFTC president and CEO. “And so, out of (the Robinson/Gantt committee) came a report. It said that civic leadership should join the first mission of the foundation, which was building philanthropic assets.”

One focus of this engagement was the environment. Foundation For The Carolinas had been trying to promote a greener, cleaner environment for the region for years, but its leaders were growing frustrated that their efforts weren’t getting more impactful results.

“The Foundation was trying to work in the environmental space before a lot of corporations and donors were involved in any big way,” said Marsicano. “And what we found back in the late 1990s and early 2000s was that we were making $30,000, $40,000, $50,000 grants to different environmental organizations, which at the time were nascent. We were making everybody feel good, but we were not moving the dial at all.”

And then came a transformative idea: When Lucille Puette Giles bequeathed the foundation an extraordinary $35 million in 1996, her only stipulation on the unrestricted gift was that it benefit Mecklenburg County. But since unclean air and polluted waterways don’t stop at county lines, Giles’ funds could be used in FFTC’s environmental efforts.

However, improving the environment is both a noble idea and a vague goal. FFTC needed specifics. Rather than dictate what the Foundation would do with the Giles gift, they decided to ask citizens: “What do you want?”

The Foundation used some of the Giles grant money to hold town hall meetings across the region to see what the communities in its 13-county region wanted.

“Over and over again, the feedback from all those sessions was greenways, greenways, greenways,” Marsicano said. “The entire region wants greenways.” And why not? Andy Kane, long-time land and trail stewardship associate for the Carolina Thread Trail and Catawba Lands Conservancy, calls them “linear parks.”

Connecting the region

Marsicano saw this as more than an environmental mission. He wondered: Is this a chance to unite the region?

“Out of those conversations, the idea emerged to create a multi-county greenway system,” he said. “And we began to put together what that might look like. Each county would design its own greenway system – but it had to connect to the contiguous counties.”

A family enjoys a creek on the Carolina Thread Trail.

Dave Cable, the first executive director of the Catawba Lands Conservancy and Carolina Thread Trail (as the trail system came to be called), had been involved since the beginning. “Community self-determination was a key factor in getting buy-in,” he said. “Each community got to decide what their part of the trail would look like.

“We literally went on the road. We did 75, 100 – I can’t recall how many – presentations. But we were out covering the 15 counties of the Thread Trail footprint, meeting with individual groups, Rotary clubs – building support, building champions. And we weren’t saying: ‘Hey, here’s a grant possibility from Charlotte; are you willing to buy into this?’ It was more like, ‘Hey, here’s a potential vision for the region. Do you want to be part of this and determine what it looks like in your community?’”

Ann Browning, the first full-time employee of the Carolina Thread Trail, said engagement in the communities was critical to success.

“We wanted to create a vision that was special to a specific place but then also connected,” Browning said. “Stakeholders came together and worked on their county’s plans and then talked to neighboring counties to figure out where the networks would connect. It was a wonderful model that was informed by those early conversations.”

There were two big ideas behind this new effort – regionalism and access to nature.

Finding a home for the trail

After the master plans for each of the counties were complete, there were 1,500 miles of trails proposed. The Carolina Thread Trail was on its way to becoming a reality.

There were two reasons for the name. One, it stands for a thread connecting everyone. The name also harkened back to the region’s history and its connection to the textile industry. “We took that concept of a thread uniting people,” Marsicano said.

Next, the Foundation looked for an organization that could pull the project off. “We thought the Catawba Lands Conservancy had enough infrastructure to take this on – with our help,” said Marsicano. “We dropped the (smaller environmental) grants program and put that entire pool into the Thread Trail (funding $500,000 a year for multiple years).”

More funds were needed. Getting the right people onboard early was crucial, and FFTC enlisted the help of its board.

Ruth Shaw was the board chair at the time, and “she’s the consummate fundraiser,” Landess said. “The Thread Trail was just an idea at that point, but having FFTC making the ask said to people: Your money will be safe.”

By the time Foundation For The Carolinas began fundraising in 2007, they had already been working on the project for three years. Bank of America and Wells Fargo (then-Wachovia) both led with twin $4 million grants.

The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation came onboard early. Dave Cable said it was like getting the Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval. “Getting the support of Susan Patterson (former Knight Foundation program director for Charlotte) right out of the gate was pivotal,” he added. “She gave us $1 million of, basically, venture capital. We were just in the drawing board stages of it, but she saw the vision.”

Bringing others along

“We were having a difficult time trying to get community leaders to really envision what this could be,” said Foundation Executive Vice President Brian Collier, who joined FFTC in 2007. “Not only that, but individuals were also seeing it through a single lens. Some were seeing it as a way for people to move around the community. Some were seeing it as a means to get people exercising. Some saw it as social capital.”

Spencer Mountain River Access is one of many blueways that are part of the Carolina Thread Trail.

As Collier explained, the trail was all of those things, working together – and that was the hard part to grasp: “We needed to lead people not to think of it as just a trail or a greenway.”

Counties and municipalities are not monoliths. Sometimes, there were factions within those jurisdictions that opposed, or approved of, the trail system. Some leaders thought it sounded like a Communist plot, recalled Cable.

“A couple of the county board meetings where I presented, there were pockets of people who were very concerned that this was some sort of governmental takeover,” he said. “But it came back to this concept of community self-determination. This was an invitation to participate – nothing more.”

One of Cable’s fondest memories of those early days happened in Gaston County, showing Marsicano’s goal of “uniting the region” might be possible.

“We basically had the political leadership for all 13 communities in Gaston County sitting around the table, and someone said, ‘Do you know how incredible this is that we’re all together? We’ve never, ever sat around the table to decide anything. And now, here we are coming together from a place of unity and strength,’” Cable recalled. “That was a really cool moment.”

Something made to last

A year after launching the Carolina Thread Trail, in 2008, FFTC formally established its Center for Civic Leadership (later renamed to honor Sally and Russell Robinson). The lessons learned from the Thread Trail initiative – convene partners to study the issue, take your findings to the community, create a plan to address the need, pool resources, create a coalition and then see the idea to completion – were infused in RCCL’s work.

The Robinson Center for Civic Leadership is located at FFTC’s headquarters at 220 North Tryon.

In the Robinson Center’s first 10 years, nearly $10 million in civic leadership funding was leveraged to generate a total dollar impact of more than $380 million in the community.

Project L.I.F.T., which was launched to improve graduation rates in West Charlotte; Read Charlotte – an initiative to improve literacy rates for area third graders; Leading on Opportunity, which is working to improve upward mobility; even the COVID-19 Response Fund, an emergency measure to provide relief to the region’s most vulnerable during the pandemic – all were initiatives helped launched by the Foundation through the RCCL.

Bringing people together is part of the role FFTC usually plays. “That’s coupled with high-level logistical support to ensure the talk turns into action,” Collier said. “And then some type of experience where people have an opportunity to see something, so that their sense of a project goes from being very small to hopefully something much bigger.”

The Carolina Thread Trail will (theoretically, said Marsicano) last longer than anything else FFTC has helped create. He calls it “the crown jewel of what the Foundation can do.”

“Eventually art buildings will come down,” he said. “Eventually, affordable housing will be rebuilt. Theoretically, the greenway system will last forever. So, one could argue it may ultimately have the greatest civic impact over generations than anything we’ve done.”

It’s a permanent ode to trailblazing visionaries and the power of collaboration. Much like embarking on a new trail in the woods, no one quite knew back in 2006 where this path would lead.

Find out more about all of the Robinson Center’s civic initiatives: fftc.org/our_initiatives